Staff Sergeant Bruce Mathewson, Jr., distinguished himself on his last day with actions and leadership that earned him the Navy Cross. It was awarded to him posthumously: the medal itself was given to his son, Earle, who had just turned two before his father died. Accounts of Bruce's final day constitute the most fascinating components of his personnel file and other documents I've received from the National Archives.

|

| The citation for Bruce's Navy Cross. |

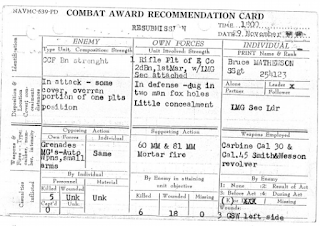

The citation for Bruce's Navy Cross doesn't come up until page 330 of his 530-page OMPF, and I first came across the faded type-written document back in May when I was furiously skimming his files. A few pages later, there is a "Combat Award Recommendation Card" that offers a few more details of the event. It mentions that Bruce died of three gunshot wounds to his left side, that he was operating in a place with "Little concealment" and acting as a light machine gun section leader. It indicates that he employed an M1 Carbine and a Smith & Wesson Revolver.

|

| Combat Award Recommendation Card found in Bruce's file. |

The card also lists two witnesses: Sergeant Lewis Patton and Corporal Joseph Sturla. Their statements indicate that his leadership (namely, directing the fire of the guns) was key in defending the position as Chinese troops tried to overrun it. He exposed himself to enemy fire as he moved from position to position. And when a small number of enemy troops penetrated the lines, he threw down his jammed Carbine and instead charged them with a pistol.

Patton's account states that "Of our group, Sturla and I were the only survivors."

There was more about this incident in other Marine files found at the National Archives. I had the chance to read reports prepared by the regiment as well as battalion in which Bruce was serving as a machine gun section leader (attached to E company). The attack on this portion of the hill took place late in the day, around 6 pm. Chinese forces thought the position Bruce's section was leading was a weak link in the American defenses. They attacked it thinking that it had been left essentially unmanned by a platoon that had been escorting the wounded.

|

| Segment from a unit history detailing the attack on November 29. |

The attack began with bugles and whistles. The attack featured a battalion of Chinese troops, with one company leading the charge into the position. Many of the Chinese troops were armed with Thompson submachine guns. The attack was repulsed and it cost the Chinese approximately 150 dead. Bruce was one of about a half dozen (I've seen accounts listing 6 and 8 as the number of dead from the company) Americans who died repulsing the attack.

Stepping back a little bit further, one should know that Bruce's death took place during a furious battle at the Chosin Reservoir. Perhaps you've heard that name before. Chosin Reservoir has an iconic meaning in Marine Corps History: though surrounded, the 1st Marine Division fought back furious attacks by the Chinese and North Koreans as they, and an exposed Army division, made their way back to relative safety near the 38th Parallel. The battle here was necessary because American forces had been pushed back by China's entry into the war. United Nations forces, who were on the verge of conquering the whole Korean Peninsula, found themselves outnumbered and overextended near China's border. The action at the Chosin Reservoir, which occurred in November and December 1950, occurred as the last American units avoided a rout.

The conditions were horrid: very cold and in rugged terrain.

Their brave stand inflicted hideous casualties on the Communist forces and made it possible for the UN to stay in Korea.

A stalemate settled in over the Peninsula shortly after Chosin Reservoir, and the battle line remained relatively fixed for three more years until an armistice was signed, allowing for a South Korea to grow and prosper.

I'm appreciative of how this research project has given me a chance to know more about a conflict that was in a bit of historical blind spot for me.

Comments

Post a Comment